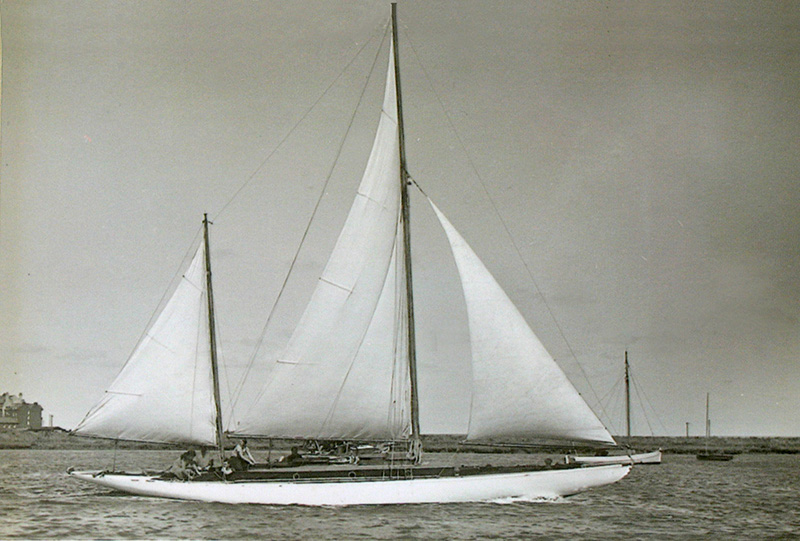

Edie II. Our family 49′ ketch was built by Summers and Payne in Southampton in 1905 as one of five “Linear 36 Footers”. In summer 2019 brother James read this in an ancient copy of “le Yacht” (19 Aug 1905 – No 1432): “Edie II” was designed by the young A.E. Payne for Colonel Robin – “un tres elegant bateau”. She had a heavy lead keel, flush decks, and a massive sail plan: a huge gaff-rigged mainsail, a topsail, and three foresails.

Before the First World War she raced in Regattas on England’s South coast and in France at Le Havre and Trouville. James found that Beken of Cowes still had an intact glass photographic plate of her when he asked for a copy over sixty years later.

Betty Carstairs. After the First World War Marion Barbara Carstairs (“Betty” Joe) bought Edie II, renamed her Sonia and raced her on the English East coast. On coming into her enormous inheritance from her grandfather (Standard Oil – Esso!) in 1921, she came to Cowes and commissioned Sammy Saunders to build her a succession of racing power boats. She was highly successful, at one time being the fastest woman on water, with her engineer, Joe Harris.

Even a century later she seems colorful by any standards. She hated the nickname “Betty”, went by the name “Joe”, usually dressed as a man, had tattooed arms, loved machines, and enjoyed adventure. She was openly lesbian and had affairs with the greatest actresses of her day including Greta Garbo, Tallulah Bankhead, and Marlene Dietrich. Around 1930 Carstairs tired of Edie 2 and ordered her destruction – probably by scuttling. Understandably, the boatyard was reluctant to follow this order and compromised by “salvaging the lead”. They cut off much of wooden keel as well – which markedly impaired her upwind sailing performance for the rest of her life.

Whale Cay. In the 1930s Carstairs became enchanted with the Bahamas and bought Whale Cay in 1934 where she reigned more or less as queen. In 1940 a group of American tourists rowed up to a beach on the island. They were met by Bahamian inhabitants, faces painted and machetes in hand, led by Carstairs waving her largest cutlass. They were taken as prisoners to the island’s lighthouse where Carstairs re-emerged, dressed as a ‘Great White Goddess’, and the locals danced and chanted around her. The tourists spent the rest of the night locked up, and were released at dawn. There was neither explanation nor apology.

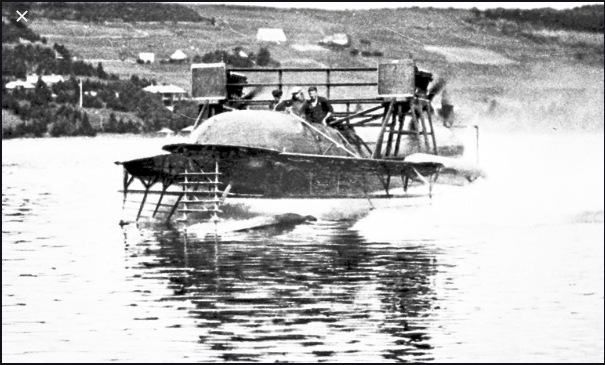

Alexander Graham Bell and Hydrofoils. Carstairs made many attempts on water-speed records and commissioned many boats, called “Estelle 1”, “Estelle 2”, etc., that were powerful and very fast. She had some great successes and spectacular boating accidents – fortunately none of them critical.

She also made firm friendships with many famous people including Alexander Graham Bell. He too was fascinated by speed on the water, created many hydrofoil-born boats, and even discussed creating one powered by sail. Apparently, Bell anticipated by some fifty years our family-based successes in Icarus, our hydrofoil-born catamaran.

Hydroplane “Baby Ino”. Soon after the First World War my grandfather and his children developed a passion for building and racing outboard hydroplanes. They achieved 24 knots on the Welsh Harp (420 acre Brent Reservoir) just North of London. (About 40 years later I made my then girlfriend – now my wife – help break ice on the same lake so that we could compete in a sailing race). When Grandfather invited suggestions for naming his larger motor boat and his hydroplane, daughter Evie replied “I know”. He liked her suggestion so much that the two boats became “Ino” and “Baby Ino” respectively. In the early 1930s grandfather redirected his passion from power to sail. After WWII we found Baby Ino disintegrating, leaning against the house in Aldeburgh. It must have hurt, but the family decided to make a bonfire to destroy her.

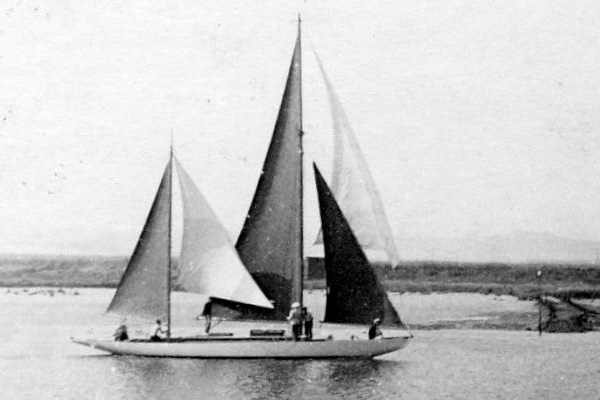

Sonia with Small Rig. In the late 1920s Sonia was found in a mud berth in Tollesbury, Essex and was towed around to Burnham on Crouch by a yard owner there. Grandfather acquired her for £225 and the yard owner refitted her with a much reduced keel. A colorful family story was that he cast the keel in the sand and floated Sonia down on to it as the tide fell. However, this wonderful idea seems unlikely and he probably did it ashore – though even that would have presented a challenge. Grandfather enlarged the cockpit, raised the coach roofing to provide much needed headroom, and added a small ketch rig. This unlikely assembly created a very fast boat off the wind but with little ability to sail upwind. This did not deter father who, in his early twenties, sailed with a brother and two friends across the North Sea to Amsterdam.

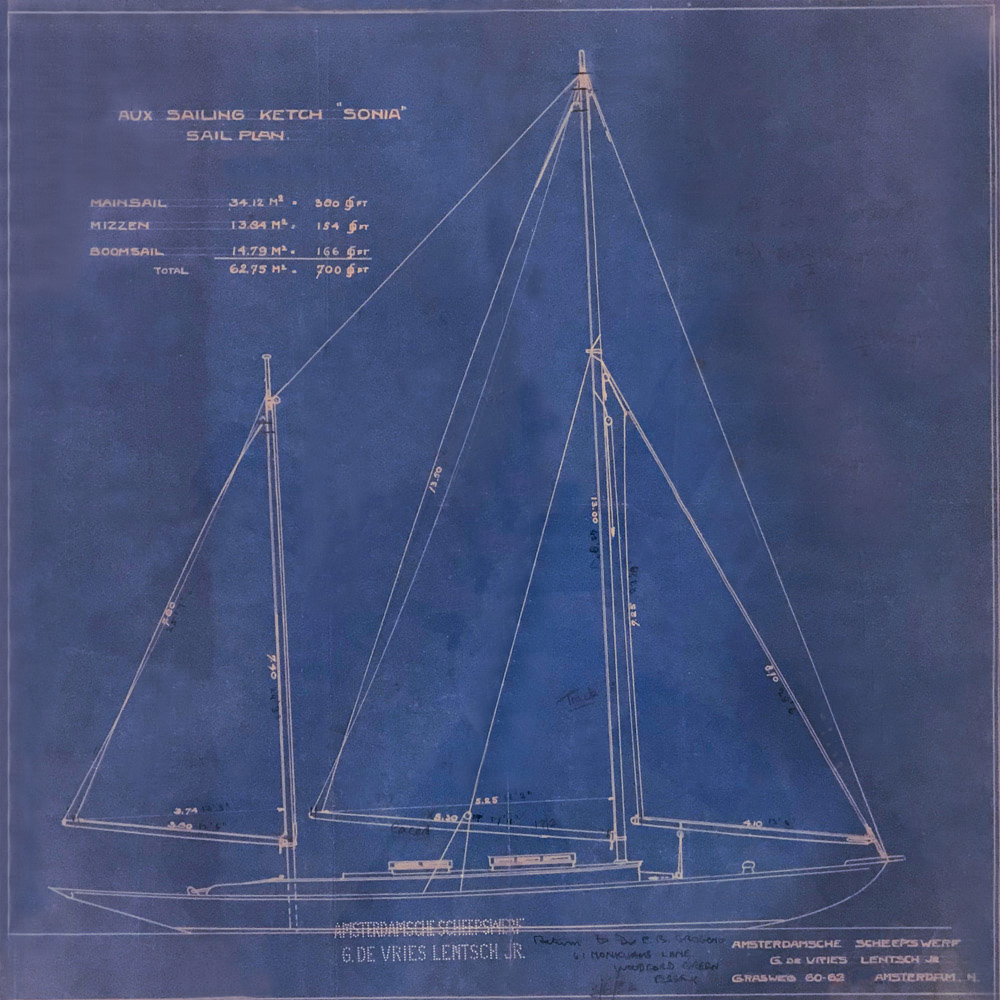

A New Larger Rig. The Port of Amsterdam taught them an important lesson. The Rules of Navigation theoretically grant priority to sailing vessels. However, such rules meant little to a commercial tugboat captain in a busy waterway. Father was resting down below when all hell broke loose; a long steel cable stretched tightly between tugboat and barge sliced away everything about a foot above the deck. He sustained a gash on his head and his brother Keith was knocked unconscious. They spent the next several weeks in Amsterdam re-rigging her with taller masts and larger sails. At the same time an elm keel was attached below the lead one – not above the lead which would have been preferable. She did, however, sail much better with these improvements. The new working sails were tanned to extend their life. However, Grandfather still had the white sails from the smaller rig and, in the right conditions, he would sail up the river Alde carrying every sail he possessed.

Another Mud Berth. Soon after the start of World War II the family faced reality. The war stopped all recreational sailing and Sonia was taken up the river Alde to Iken. At the top of a Spring Tide she was allowed to settle down once again into the mud where she remained safe for the next six years.

Moored in Aldeburgh. Back down the river again Sonia was one of the larger yachts in the anchorage with a permanent mooring just opposite the old Martello tower – a relic of defenses against Napoleonic France. Once a year at high tide we took her alongside the jetty and secured her there propped out from the concrete to allow us space to work all around her. At low tide, the whole family would scrub off barnacles and seaweed and apply a coat of antifouling paint. Among the jobs I never wish to do again, that must be at the very top of my list.

This photo shows a Thames Sailing Barge in the distance. For many years after the end of the war they still carried cargo up and down England’s East Coast. They usually had a crew of two and, initially after the war at least, they had no auxiliary engine and relied on wind-power only.

Exciting Family Picnics. With a reaching wind and a falling tide, the ten-mile journey down the River Alde only took about an hour. Down at the mouth of the river there was a shingle bank between river and sea. The shingle was, on the river side, extremely steep and at mid-tide sharp ears could hear the strong tidal current fashioning the shingle. This shore was steep enough to mean that a keel boat could almost come alongside. Instead we aimed Sonia’s bow at the shore with Father, anchor in hand, on the bow. He then stepped ashore and carried the anchor far enough up the bank to allow for the rising tide.

Ashore Mother would lay out the picnic and the rest of us would collect anything that might burn: driftwood, paper, coal, fuel coke and dead plants. In an astonishingly short time we would have a huge bonfire. Cool English summer weather meant that we appreciated the warmth as we ate.

In later years younger brother Andrew would demonstrate his pyromaniac skill by launching smaller bonfires on a pieces of driftwood. Fortunately none of them ever drifted near the boats.

On the Mud Again. Navigation in the Thames Estuary could be somewhat uncertain, at least for us. On one trip with a medical school friend, Don Woodgate, Sonia was on the mud once again and this time the tide left her high and dry. We walked around her confident that she would eventually re-float.

As the tide returned we noticed that she seemed somewhat less buoyant than we had expected. Clambering back on board we found out why. The flexing of our ancient boat had separated the hull from the engine’s exhaust pipe. Indeed, where the pipe should have been there was now a two inch water fountain rapidly filling the boat. Fortunately, insertion of pyjamas and shirts stemmed the flow and she re-floated as planned.

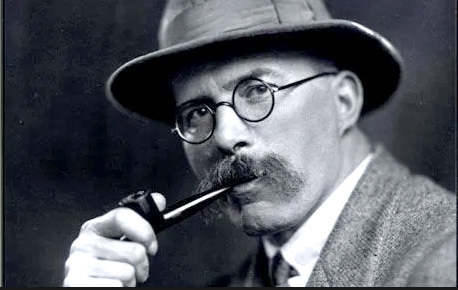

Arthur Ransome. In retrospect my parents’ trust in their three sons seems astonishing. In addition to letting their three sons manufacture fireworks, Father and Mother also allowed us extraordinary freedom to sail up and down the East Coast, cross the Channel to France, and cross the North Sea to Holland. Today, when we are measurably safer, we are scared of our own shadows and obsessively guard our children. In the wake of WW II Father and Mother had us reading books by Arthur Ransome. He described wonderful adventures by children and, in “Swallows and Amazons”, penned this memorable advice: “Better drowned than duffers, if not duffers won’t drown.” Father certainly liked this advice more than Mother.

Ransome himself was, like Carstairs, extraordinary by any standards. He travelled to Russia in 1913 where he married Trotsky’s secretary. He acted as a reporter but also became a vocal champion of Lenin’s government. As a reporter he lied, reassuring British readers that the Bolsheviks were doing their best to keep bloodshed at a minimum. To quote a reviewer’s tongue-in-cheek summing-up: “Soldiers were shooting their officers, yes, but they did so with admirable restraint.” Many British officials considered Ransome a Communist. However, no other Brit could come close to matching his Kremlin access, and so – as shown by MI5 archives made public in 2005 – MI6 recruited him in 1918 as a spy. Soviet archives also shed light on Ransome’s story.

One question that still remains, however, is whether he was actually a double agent –a man whose ultimate loyalty was not to London but to Moscow. Admittedly, there’s no absolute proof either way. But we do know that he and his wife Evgenia smuggled diamonds from the USSR to help fund the Communist movement in Western Europe. We also know he owned a lavish yacht that must have cost a bundle – more cash, certainly, than most British reporters would have been able to scrape together, and more, apparently, than could be accounted for by his MI6 paycheck. In “Divided Loyalties” one observer asked whether the money had been earned from the INO, an intelligence-gathering branch of Felix Dzerzhinsky’s sinister Cheka.

Sonia’s History. While researching for this page I found another 49ft Summers & Payne Cutter “Hardy” – built five years later than Sonia and being restored by boat builder and restoration specialist Jamie Clay. Her 11 ft beam is nearly two feet greater than Sonia’s which would make her significantly more comfortable. I am most grateful to Jamie who was also influenced by Arthur Ransome. Jamie’s grandfather was a professor of economics at Manchester university, and met Arthur Ransome as both of them wrote for the Manchester Guardian newspaper. They later met again on their boats on the East Coast. The boat Jamie sails, Firefly, was bought by his grandfather in 1934. One of the dinghies in Ransome’s Secret Water is called Firefly, and We Didn’t Mean to Go To Sea is dedicated to his grandmother (Mrs. Henry Clay) who initiated idea of sending the ‘Swallows’ on an adventure across the North Sea.

Jamie spent several hours searching through his copy of Lloyd’s Register of Shipping to find these details about our Sonia. Lloyd’s relied on the owners of the yachts to fill in a form every year. The first year it was probably done by the builder, and accurate. Thereafter, it tends to become less so.

1906: Edie II first listed as built in 1905 for Colonel P. Robin (resident in Jersey). Her dimensions are given as 41.5 length x 33.44 waterline x 9.2 beam. 15 tons TM . Very misleading as at this time, Lloyds only gave the ‘Thames length’ between stem and sternposts (omitting overhanging sterns) and this number was also used in the formula to calculate the Thames tonnage, which was in fact a volume not a weight. She is listed as designed by A.E. Payne jun., and built by Summers and Payne at Southampton. The linear rating of 36 is also given, so clearly she was built with racing in mind.

1910: Renamed Sheila and owned by Lt-Col C.E.M. Pyne at Southampton.

1914: New owner D. Hanbury, Southampton, and the WL is given as 36ft.

1920: Now Sonia. New owner Maj. H. Maitland Kersey D.S.O. Southampton.

1923: New owner Miss Marion B. Carstairs of Christchurch (Sails by Ratsey and Lapthorn 1922, Area 990 sq.ft.) Carstairs also owned a 2 ton motor vessel and the 114 ton screw schooner Vergemere II converted from steam to oil.

1926: More new sails.

1934: Now listed as aux. ketch length 41.5 x 49.5 x 34.5 x 9.2 beam x 5.7 draft sail area 540 at Burnham on Crouch, owner Eric Grogono, LRCP MRCS of 171 Romford Road, London E15. Clubs belonging to; Ald. Cor. U-Hs. These are the abbreviations for the Aldeburgh Yacht Club, the Royal Corinthian Yacht Club (at Burnham) and the United Hospitals Sailing Club.

1954: Sail area increased to 660 sq.ft.

1963: New owner E.L.J. McConkey of Birmingham

1967: Last entry.

Still Part of the Family. Many years have passed and there have been many other adventures – some of them with Sonia. Even though our children and their cousins never knew her, Sonia is still remembered in our family – known by legend, pictures and reputation. Our older son David’s daughter is named “Sonia” and our younger son Martin has this Amsterdam sail-plan framed in his kitchen.

Alan Grogono