Safety

Rope, and sports associated with rope, can be dangerous. Wrongly handled, gripped, or tied, rope can kill, maim, or burn. You could be the victim! Handle rope with care, inspect and test any knot you tie, and respect any rope subject to a heavy load, e.g., a rope controlling a large sail, a mooring rope when you are docking or berthing, and especially your own climbing rope.

Watch Your Limbs

Never stand in a loop or a bight of a rope which may suddenly tighten, e.g. an anchor line or tow line. You have two legs when you are born. Guard them. That goes for any body parts, fingers, arms, and the like, watch out for coils and small loops. Even a small line wrapped around a finger can cause serious injury when put under sudden strain. And, avoid deliberately wrapping a line/rope around your hand to get a better grip. You may find that the rope has you rather than you having it.

Control

Never try to control a heavily loaded rope or fishing line with your bare hands. Take two or more turns round a post, winch, or cleat, and use appropriate equipment for fishing line. The danger associated with heavily loaded rope or fishing line is commonly learned by experience, which is often very painful and could be lethal.

Never try to control a heavily loaded rope or fishing line with your bare hands. Take two or more turns round a post, winch, or cleat, and use appropriate equipment for fishing line. The danger associated with heavily loaded rope or fishing line is commonly learned by experience, which is often very painful and could be lethal.

Knots Weaken Rope

Because of knots, kinks, and imperfections, assume that even brand new rope will perform at no more than 50% of its rated breaking strength. And, when dealing with critical loads, it is vital to understand the magnitude of a sensible Safety Factor.

Working Load and Design Factor

The breaking strength must be markedly greater than the designed load. Although Safety Factor has often been used, Design Factor (DF) is now preferred. A compact summary is provided by the Cordage Institute Guideline CI 1401-15: “As a rule, the more severe the application, the higher the DF needs to be. Selection of a DF in the general range between 5:1 and 12:1 is recommended.”

Accordingly, for live or critical loads the DF should be 12, i.e., a rope’s breaking strength should be twelve times the load (12:1). To lift an average man, a breaking strength around a ton is indicated.

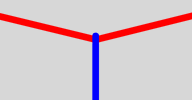

Rigging Angle

A rope strong enough to lift a given weight may be totally inadequate when the weight is hanging from the middle of the same rope stretched horizontally, e.g., when rigging a hammock. Too often the effect of such a rigging angle is not appreciated. In certain circumstances, such a mistake may be lethal.

A rope strong enough to lift a given weight may be totally inadequate when the weight is hanging from the middle of the same rope stretched horizontally, e.g., when rigging a hammock. Too often the effect of such a rigging angle is not appreciated. In certain circumstances, such a mistake may be lethal.

Dynamic Loads vs. Dead Weights

Similar concerns apply to loads that are moving. A rope stopping a falling object may be subject to a load many times the object’s weight.

Intermittent Loads

Many knots can loosen with prolonged intermittent strain. For example, a bowline just “floated undone” when Grog was swimming around scrubbing the boat’s waterline; a perfectly good scrubbing brush sank before he realized it was no longer attached.

Security and Additional Half Hitches

Mooring lines are exposed to intermittent strains and it is wise to use additional half hitches or a seizing to provide greater security. A seizing is a wrap of small line holding the tail against another adjacent part of the knot. Although a seizing may be very secure, it is a nuisance because it cannot be easily “untied”. By contrast, it is quick and convenient to add extra half hitches, and they are commonly found on the: Round Turn & Two Half Hitches, Rolling Hitch, Anchor Hitch, the Clove Hitch and, of course, the Square Knot.

Safety Knot: Climbers are particularly wary of the bowline especially when carried around at the end of a coil of rope. One technique they recommend is to use a stopper knot to secure the tail around either the standing end or the adjacent part of the bowline’s loop.

Under Load: Four knots are valuable specifically because they can be tied and untied under load: the Round Turn & Two Half Hitches; the Cleat Hitch; the Rolling Hitch; and the Munter Mule Combination. Learn these well. By contrast, the bowline is impossible to tie or untie under load.