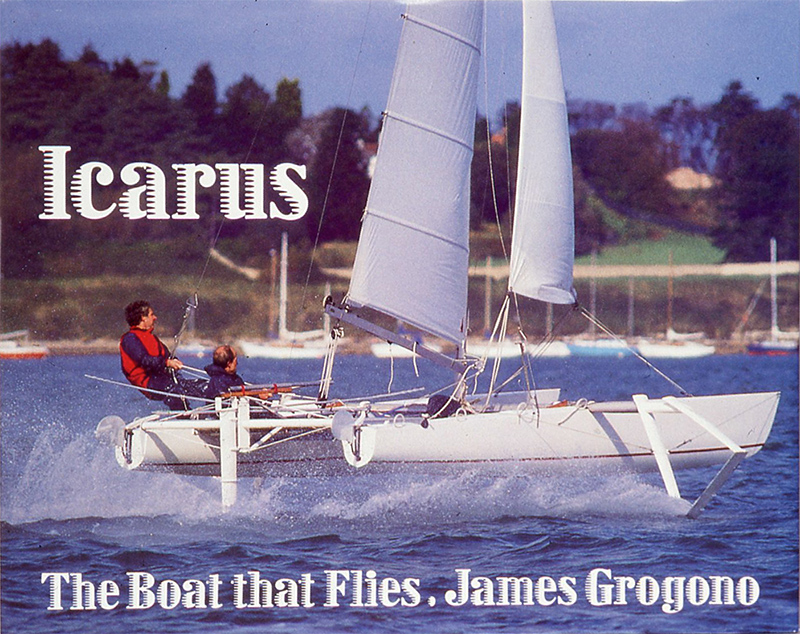

The Icarus Project. In the late 1960s and 1970s brother James led the family to embark on a project to create a World Sailing Speed Record. We named our catamaran after the mythical Icarus and fitted her with progressively improved hydrofoils.

Our success was due to James who provided the vision, the tenacity, and the leadership. Fortunately I have just revisited his book “Icarus The Boat that Flies”. I would have done him a disservice by condensing some 15 years of his life, work, and effort like this:

All of it was brother James – the whole thing. He dreamt it, he designed it, and he worked on it – initially all in secret – and finally he wrote the book (The Boat That Flies). He joined the RYA (Royal Yachting Association) and got elected to the racing committee. There he announced that there would be a Speed Sailing Competition. Because no one else knew what he meant, he planned the competition, designed the course, persuaded John Player (cigarette manufacturer) to be the first sponsor and asked the Royal Navy to allow cadets in inflatable dinghies to provide support. Then, while his fellow committee members protested, he resigned so that he would be free to compete. Quite late in this process he announced to our family (father, younger brother Andrew and me) that we were a syndicate with yachting journalist David Pelly and friend John Fowler. We asked why he had kept us in the dark for so long. He explained that he knew none of us could keep a secret. He had selected the ideal boat for modification – the successful Olympic Tornado catamaran. She was stable, fast, powerful, and allowed hydrofoils to be attached. That we did – initially making wooden foils ourselves which we screwed to the wooden hulls. Later we obtained metal ones which we attached to the much stronger cross-beams.

Foil Lift. My condensed story is more or less true but the early development was spread over several years in the late 60s and early 70s. For the detailed account I warmly recommend James’ book. copies of which may still be found via the Internet. As we worked on Icarus we were, initially, unaware of the lift we would achieve. We were also unaware of similar work in the USA by various people including the US Navy; judging by the height above water, the Navy too underestimated the extraordinary lifting force of an immersed foil. We might have guessed: a small propeller delivers astonishing force.

We were certainly unaware of the early pioneer work in the 1920’s by Alexander Graham Bell on the use of hydrofoils on power boats. His work culminated with Hydrodrome #4 (also known as the HD-4) which established a world speed record for water craft on September 9, 1919, traveling at 70.86 mph on Baddeck Bay, Nova Scotia. This record would remain unbroken for almost a decade.

The Mythical Icarus. Near the sun his feathers detached and he plunged to his death in the sea. Strictly we had no feathers but we did go very fast. Unfortunately, we also had many accidents – mercifully none involving death.

A carpenter apocryphally once said: “same old hammer” despite three new heads and five new handles. Likewise, our team always knew she was “Icarus” despite different hulls, several rigs, and a generous assortment of foil arrangements. Eventually, the only pieces that stayed unchanged were the two cross-beams that joined the hulls and supported the foils.

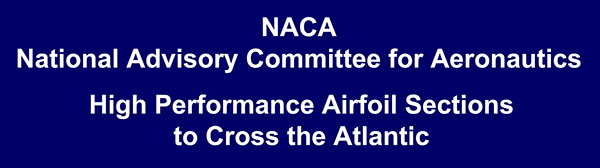

1938 Sailing Hydrofoil Experiments. The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA – forerunner of NASA) worked to perfect airfoil shapes to transport planes and supplies across the Atlantic. They produced masses of different shapes with individual performance characteristics. The Amateur Yacht Research Society Publication 19 describes how NACA team members R. Gilruth and Bill Carl experimented with foils in 1938. They successfully sailed a hydrofoil catamaran that took off at 5 knots and cruised at 12 knots. The main foil had an aspect ratio of 11:1, a 12 foot span, a 1 foot chord and the astonishingly low Lift/Drag ratio of 25:1.

NACA Foil Shapes. When we were still making our own wooden foils I used a copy of the NACA Wing Sections book to find the most efficient. As an anesthesiologist I sometimes did this in the Operating Room when everything was on “auto-pilot” and I could relax. With the book on my knee I examined each page to find the perfect lift-to-drag ratio. I think we chose airfoil section 2412 and from it we created templates to make the foils. For all I know now it could be the same section used by Gilruth and Carl. Certainly the high Lift/Drag ratio seems familiar.

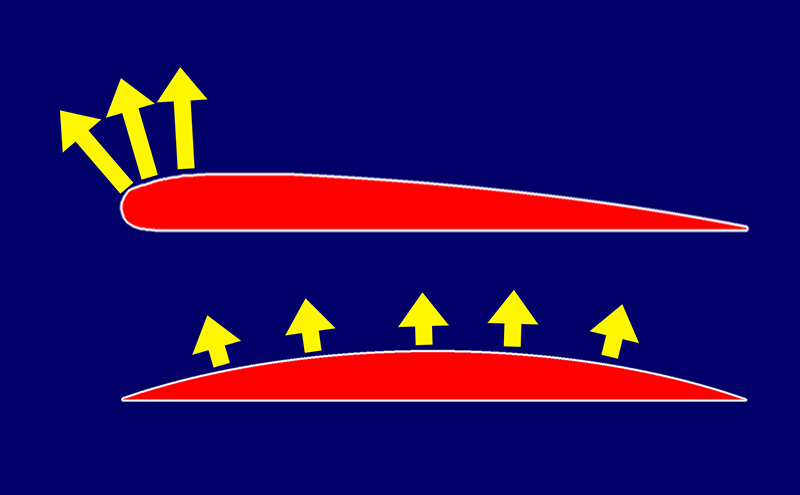

Return to Simple Curve. The chosen section had a marked upper curvature near the leading edge. For flying across the Atlantic in WWII it may have been ideal. We made a set of foils to match the shape by planing down timber in Father’s garage. The foils provided lift but as our speed increased they generated ventilation; there was too much negative pressure at the leading edge and we returned to the plain “ogival” – simple curve – upper surface..

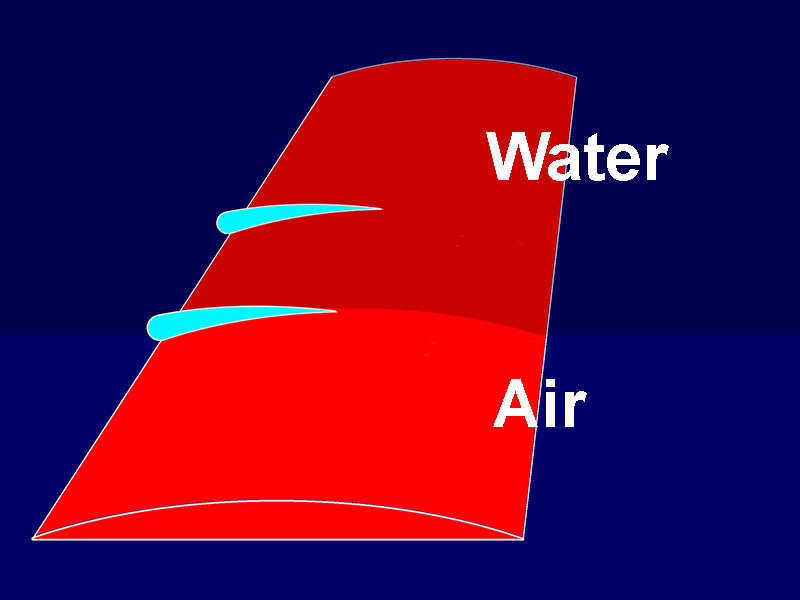

Final Configuration. We created an airplane configuration: larger fixed oblique metal wings roughly amidships and a much smaller fully immersed tail wing on the rudder for control. The slanted main foils were partly in the air and partly immersed – they were “surface-piercing” and this caused endless problems. The relatively low pressure above an airplane wing essentially provides most of the “lift”. Even with the Ogival shape this same low pressure caused “ventilation”. i.e., air was sucked down along the leading edge and destroyed the foil’s lift. We attached metal fences by various means to minimize this but they were fragile and never lasted long.

Early Disaster. Before the metal foils we positioned a wooden foil at bow and stern of each hull – an arrangement that relied on the strength of the hulls. The hulls were, of course, not intended for these stresses and when one of the foils broke free it punctured the port hull. Brother James arranged an emergency repair with plywood and large quantities of black tape. This allowed us to resume sailing for publicity and much-needed photographs. Here he is on a trapeze, sailing solo, and steering with the bow foils.

Briefly a Submarine. For some years Icarus was kept at Burnham on the River Crouch. I had solicited help from a group of medical students where I worked at the Royal Free Hospital in the hope we could create the speed record. The agreement meant that if I called them at 7:00 am they would abandon studies and meet me in Burnham. I made a similar arrangement with an official timer. Each morning I would wake very early to listen to the official BBC weather forecast. As the River flowed east/west, I looked for a South wind to give us a reach along a leeward shore. The timer and the students measured out a 500 meter course along the seawall and then helped launch John Fowler and myself. Finally, conditions were excellent and we made several fast runs fairly close to the embankment.

On our last run heading East, there was a sudden huge gust from astern. Even with the sail out completely there was still far too much power; the sail just drove the entire boat under water. Even at the stern I was up to my waist in water and we stopped very suddenly. The hulls quickly floated back up – something like a fluttering leaf in reverse and Icarus, now released, shot forward again. We were very lucky to have avoided a “pitch-pole” capsize.

When we came ashore we commented to the shore team that the final run was exciting. The response was that we probably hadn’t realized how exciting. The sudden impact compressed the mast making it briefly look like wet spaghetti. They all had assumed it must break and were very relieved when we resurfaced and catapulted forward again .

Puncturing the Navy. In Portland Harbour, the site chosen for “Speed Week”, the Royal Navy’s cadets operated inflatable dinghies. Among other duties their help allowed us to pick up a mooring buoy for a rest between attempts. They would then ferry us ashore and return us for more trials. On one trip back we warned them repeatedly about the risk posed by our sharp metal foils. We made some suggestions about where and how to make the transfer but they went unheeded. The foil made a large gash in the starboard side of the inflatable and one whole section deflated in an instant.

One of the cadets was exceedingly quick-witted and lifted up the deflated section like a curtain. To our great relief the inflatable stayed afloat and they maneuvered her back ashore, albeit rather slowly. On subsequent days our suggestions were delivered more in the form of instructions and no more inflatables were damaged..

Crossbow Kept Me Awake. On the first year of serious competition two of us, Crossbow 1 and our Icarus, were fairly evenly matched. I was in Icarus with John waiting our turn to sail with a splendid view of Crossbow on the course. She was clearly sailing at great speed and we could sense our chance at the record slipping away and then, schadenfreude – the guilty pleasure of another’s misfortune, their tall, elegant mast crumpled to the deck and we thought maybe we had a chance. Surely repairing Crossbow was going to be impossible. The critical rule was that to establish a record, you had to best the record recorded so far by one knot. We hoped to put in our run first and have the credit for that year. It was not to be.

On the night after their accident John and I planned to relax and enjoy a good-night’s rest. Instead we spent the night listening to feverish hammering and shouting outside our hotel window. Their spare mast had been delivered during the evening and was now being fitted to Crossbow to sail again next day. Crossbow established a speed that we came very close to but could not beat by the required margin.

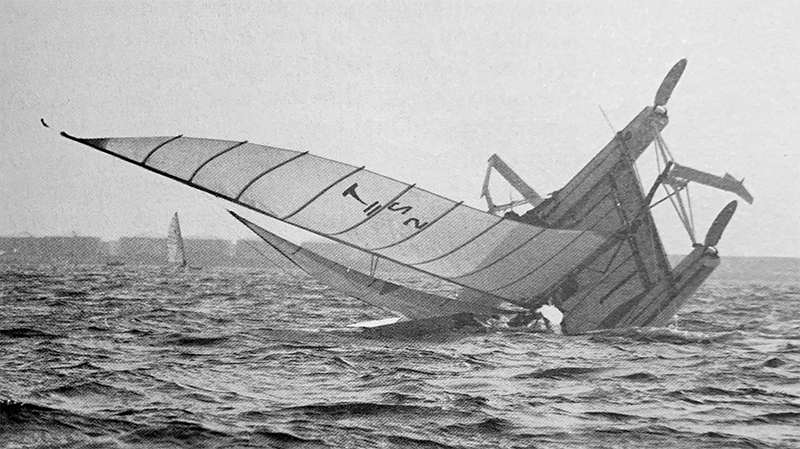

Two More Spectacular Accidents. One one occasion brother Andrew was sailing Icarus with Ian Worley. After several inadequate attempts they tightened the sheets and entered the course at great speed. The photo shows Icarus when the strain on the rigging exceeded the strength of the Port Hull and tore the front eight feet completely off. In the photo the Port Bow, still attached by its control wires, is just visible beneath the jib.

Another time I was sailing Icarus with our farmer syndicate member John Fowler. We had several runs through the course and often achieved high speeds but none that were sustained. In frustration he asked to take the helm; it was hard to refuse. I explained the major problem. In a trough between waves the main foils could find air and the bow would then skip sideways. This put a huge load on the rudder and hence the helm – a long narrow pole across the boat. He nodded and claimed he completely understood. He started on starboard tack and with some misgivings I hooked on to the trapeze wire and clambered out to stand on the side-rail. The wind was strong, at the perfect angle, and we were sailing really fast. Then the foils were in a trough, the bow skipped, and I saw the tiller whip through John’s hand. The boat turned very abruptly to port and I headed up, up to the sky. I looked down at Icarus and had a flash, a vision of falling and hitting my head against metal, the mast, the boom, or a fearsome foil. But No! Of course not! My weight pulled Icarus down on top of me. The trapeze which only a moment held me up was now my anchor in the water. The boat quickly completed the capsize and I was dragged deeper. It was brief and I managed to unhook the clip to appear beside John. We climbed on to the upside-down trampoline to await help.

I was unaware that the BBC was filming all of this. I was also unaware that my wife had promised the children that she would wake them up and let them get out of bed to watch Daddy going very fast. She did wake them and they watched. But, all they saw was me standing on the upturned Icarus.

We were still on the course and very much in the way. Soon after the capsize strong hands in a rescue boat worked their way steadily along the entire length of our main shroud. When we were ready to clime back on they threw the mast up in the air and we continued sailing.

Enriching the Family: Like other family boats Icarus enriched our lives and drew the family together. We did go fast and it was very exciting. Average speed was recorded. Each attempt included slow patches and bursts of speed. In one of these sprints I’m sure we went about 35 knots (40 mph or 65 kph) but, unfortunately, we also came off the foils and spent time sailing very slowly. For about five years we held the “B” Class World Sailing Speed Record with our mean speed reaching 28.15 knots. However, it gradually became clear that size was almost irrelevant. Much higher speeds were achieved by windsurfers and kite-boards except for 2009 when the magnificent French Hydroptere achieved 51.36 knots before her own spectacular pitch-pole capsize. She had a length of 60′ and a width of 79.4′.

Current Open Sail Speed Record: At present (2019) the record stands at 65.45 knots by Paul Larsen in Vestas Sailrocket 2 – a unique boat with a steeply slanting rig. This striking design means that the force on the sail passes through the under-water foil; there is virtually no overturning moment and no net vertical lift. Like other speed sailors Sailrocket has had some spectacular accidents, including flying into the air to nearly complete an airborne loop-the-loop.

Icarus still exists and might from sometime be resuscitated – but not by any of the remaining members of the original syndicate: David Pelly, brother Andrew, myself and our inspiration and “slave-driver” – brother James.

Alan Grogono